Sopwith Tabloid, Schneider and Baby

Sopwith Tabloid Fighter/bomber, crew 1, single-engine biplane. The fuselage is rectangular with a single open cockpit aft of the wings and a small, rounded tail fin. An air-cooled engine with a two-blade propeller is mounted in the pinched nose. Both top and bottom wings are rectangular with the same span.

Sopwith Tabloid download a 750pixel image

The wings are connected by a pair of I-struts on either side. Semi-circular tailplane is set in front of the tail fin. Landing gear consists of two large wheels mounted under the wings with two skids extending forward of the propeller. The landing gear is unretractable.

Sopwith Tabloid

Sopwith's first fighter, "Tabloid" was first flown in 1913. Originally designed as a sports aircraft, "Tabloid" fitted with floats participated in the prestigious Schneider Trophy race of 1914, which it won, setting the speed record at 148 km/h. "Tabloid" fitted with wheels was even faster. Around 40 of these aircraft were built and they saw little use in the beginning of the World War I.

Sopwith Tabloid download a 500pixel image

Sopwith Tabloids under construction at the Sopwith factory Also on right can be seen the hull of a Sopwith 'Bat Boat' download a 750pixel image

Sopwith Tabloid promotional card, Atlantic Union, 1958

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane, Sopwith 'Schneider' The Sopwith Schneider was developed from the Tabloid in 1913. The Tabloid was a revolutionary small 2-seat sports plane that used all the latest technology in a sensible mix. It was immediately nicknamed the Tabloid, due to it's small size. It turned out to be an extraordinary fast machine for the day, so plans were made to enter it in the 1914 Schneider Trophy race. Now fitted with an 100hp Gnome monosoupape engine, it was mounted on an enormous flat single float, but overturned on the first attempt at taxying on Southampton water.

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane

They managed to rebuild it in time for the race, this time on two small floats, mounted further forward, after a short flight from the Thames it was shipped to Monaco. The competition consisted of Nieuports, Moranes, Deperdussins and an FBA. The Nieuports were the favorites, but the Sopwith was a complete unknown, even to the Sopwith crew, they had hardly flown it. The first off were the two hot Nieuports of Espanet and Levasseur, they were lapping at 67 and 58mph, then Pixton in the little Sopwith started, followed by the Swiss entry Burri in the FBA. Pixton immediately started to post amazing speeds, up to 89mph, the opposition was shattered, none of the others could have approached that speed even in ideal conditions. In the end all but Burri and Pixton dropped out, and Pixton won the Schneider trophy with more than an hours margin.

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane http://pilots-n-planes-ww1.com

The First World War broke out shortly after, the Tabloid was quickly ordered for military use, and eventually so was the floatplane version. The Schneider Trophy design was put into production with only minor changes. The rear fuselage was made detachable and the floats were redesigned, strangely wing-warping was retained despite the Tabloid already being fitted with ailerons. New modifications were made to each batch produced, proper ailerons were soon fitted. A larger fin and improved floats were other changes. With the change to a 110hp Clerget came a new name, the Sopwith Baby, and later on Babies were made by other manufacturers thus becoming Hamble Babies, and Ansaldo Babies for instance.

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane download a 750pixel image

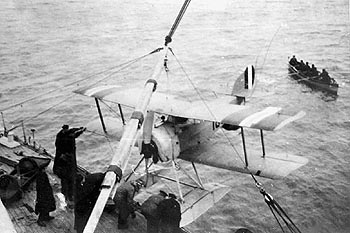

In service the Schneiders were mostly used for patrol work, but attempts were also made to deploy them aboard the seaplane carriers Engadine, Ben-my-Chree and Rivierra. These deployments were mostly unsuccessful, as were attempts to intercept Zeppelins. It certainly pointed the way towards future developments and that is perhaps what the Schneiders service career should be remembered for. Though initially the Schneider retained a triangular fin, as on Pixton's racer, this surface was later much enlarged in area (as was common with floatplanes) then being curved in contour; and this development was commonly associated with the fitting of ailerons instead of a wing-warping system, though the latter was used on the early Schneiders. An especially noticeable difference-even on the early Schneiders-was the additional diagonal strut in the float-attachment assembly (a feature that was to recur in the Schneider's lineal descendant the Hawker Nimrod, though in that instance respecting the center-section struts and not those which attached the floats)....more

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane, Sopwith 'Schneider' Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane, Great Britain's first Schneider Trophy winner in 1914. T.O.M. Sopwith -- who, together with Frederick Sigrist, designed and built the Tabloid in 1913 -- is one of the world's most famous pioneer airmen. He held one of the first pilot's licenses ever issued. During official trials, the Tabloid achieved a maximum speed of 92 mph, with a stalling speed of 36.9 mph.

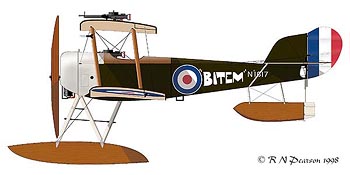

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane Sopwith Aviation Co. by Bob Pearson http://www.internetmodeler.com

From his own experience of air racing, Sopwith knew this plane's value in terms of publicity and as stimulus to aircraft engineering and aerodynamics development. Accordingly, he modified an early production Tabloid as a seaplane for the Schneider contest due to take place at Monaco on April 20, 1914. The Tabloid Seaplane helds it first serious flight on April 19, and it was found to need a larger propeller due to the Gnôme engine running too fast. Sopwith and pilot Howard Pixton expected the Tabloid to fare well in the race, but the tiny plane's performance exceeded even their most optimistic hopes. Pixton crossed the finish line after twenty-eight laps and a total distance of 174 miles in a time of two hours and thirteen seconds -- an average speed of 86.75 mph. Pixton then opened up his motor and completed another two laps at still higher speed, breaking the world's record for seaplanes with a speed of 92 mph for a distance of 186 miles.

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane

The 1914 Schneider Trophy The following report was first published in a newspaper in 1914, just after Howard Pixton had won the first Schneider Trophy. On April Fool's Day 1914, an anxious team of British engineers, handlers and aviators tested the new float system on their entry for the second Schneider [Trophy] race. The little biplane was positioned at the end of a high water jetty on the Hamble river as the tide came in. The pilot, C. Howard Pixton climbed into the cockpit and started the engine. The tide was within six inches of the jetty. The team pushed the aircraft over the edge.

The Schneider Trophy

As Pixton started to taxi, the aircraft promptly cartwheeled proving that the main float had been fitted too far aft. Pixton was flung clear. The aircraft, a Sopwith Tabloid, sank, drifting upside-down out into midstream. The disconsolate team eventually got a rope on it, and the next morning dismantled the sodden, buckled machine, now stranded by the tide, balancing on its nose with its tail in the air. Redesigning and rebuilding would have to be fast. A fortnight later the Sopwith Tabloid was unpacked and reassembled in the team tent at Monaco. It was the smallest and lowest-powered aircraft in the race, and the French, feeling secure in their dominance of world aviation by this time, ridiculed the British team as they laboured over the still rusty engine, refusing to believe the rumours that the little biplane had already achieved 92 miles an hour in tests.

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane, Schneider Trophy, 1914

Early on Sunday 19 April, the French began to look more thoughtful after watching the Tabloid's test flight. The aircraft had clumsy makeshift floats and a peculiar 'sit' on the water. However, its take-off was smooth and swift compared with the sluggish performance of the French mono-planes. Monday 20 April, was race day. Under the rules, each competitor had to make two alightings and take-offs during the first lap though these could be in the nature of a landplane's circuits and bumps, without stopping. The two French Niueports were first away, followed by an FBA flying boat flying for Switzerland. The FBA excited the crowd with a long, porpoising take-off, beginning with a series of hops and finally bounding and ricocheting into the air.

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane, Schneider Trophy, 1914 Pilot C.Howard Pixton is on the port float

Pixton took off in the Tabloid a quarter of an hour after the two Nieuports. Opening the throttle, he was accelerating rapidly as he crossed the starting line, and his floats actually left the water only 50 or 60ft beyond it. There was a moment when the machine faltered, the floats bounced once on the water, and then the little biplane was climbing strongly away, heading into wind down the long leg of the course towards Cape Martin. At the sharp turn Pixton banked steeply. Then, with very little reduction in speed, he came down low and his floats kissed the water twice. It was a beautiful piece of flying, and the Tabloid seemed to be slowed by the contact hardly at all.

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane, Schneider Trophy, 1914

The Sopwith biplane was obviously faster and more manoeuvrable then the monoplanes. At the announcement of its first lap time, the crowd whistled in amazement. Pixton had taken 4 minutes 27 seconds, half the best French time. Six agonising laps By the halfway stage both French Nieuports were having engine trouble from the strain of chasing the Tabloid as the rear banks of their twin-row Gnome engines heated up. Both ended up with seized pistons, leaving the race to Pixton's Tabloid and the Swiss FBA.

Sopwith Tabloid Seaplane, Schneider Trophy, 1914

Some participants, disheartened by the Tabloid's apparent supremacy, had refused to start the race. They began to think again when, on his 15th lap out of the required 28, Pixton began to suffer misfires in one of the nine cylinders of his 100hp Gnome Monosoupape' rotary engine. Pixton's lap tirnes now began to rise a few seconds at a turn. For six agonising laps the drama went on. One by one Pixton ripped out the drawing pins which were his crude lap counter. Then the Gnome settled down on its eight good cylinders and the lap times improved again. Throughout the final lap Pixton and the Sopwith Tabloid were applauded. With an average speed of 86.78 miles an hour they had beaten Prevost's true average of the previous year by 25 miles an hour.

In 1914 the winner of the Schneider Trophy was one C. Howard Pixton. An intrepid aviator; his career started in 1910 at Brooklands, the Mecca of experimental flying, where he became A.V.Roe's friend and right hand man. He started the AVRO School of Flying and was AVRO'S first test pilot. In 1911 he joined Bristol's and in that year he earned more prize money for flying than anyone else in Britain and taught many of the early Army officers to fly.

After his win he was commissioned as a Captain in the R.F.C. and joined the Air Investigation Dept., at Farnborough. In 1914 he joined Tommy Sopwith and won the Schneider Trophy at Monte Carlo

C. Howard Pixton center, with Thomas Sopwith on right The person on the left is ?

The 1914 win was Britain's first international victory with a British plane, which gives Howard Pixton the status of being the man who put Britain in the lead in aviation for the first time. After the war he rejoined A.V.Roe and among other things he, for the first time, flew newspapers to the I.O.M. and flew the first fare paying passengers from the I.O.M. He retired to the I.O.M in 1932 and became a leading figure on the Manx aviation scene. During the 1939-45 war he rejoined the AID at Farnborough and was 60 when the war ended. He died in 1972 and is buried at Jurby Churchyard. for more about the Schneider Trophy see... http://www.manx-modelflyers.org

http://www.europeansportpilotassociation.com

Sopwith Baby The three-float single-seat Sopwith seaplane which, in November 1914, was put into production for the RNAS was-as the commonly used name 'Schneider' proclaimed-very much the same aircraft as the Tabloid floatplane with which Howard Pixton had made history at Monaco in the preceding April - still with the relatively powerful 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape engine (though not specially tuned) on the 'nose-bearing' mounting.

Sopwith Baby

By noting that the name Schneider was 'commonly used' one has in mind the quite extensive currency-in official and private documents alike-of the appellation 'Schneider Trophy [or Cup] seaplane'. For was it not vastly glamorous (and good for recruitment) to be able to assure one's girl-friend that one was flying 'a real racer' of such high renown rather than just 'a little seaplane' especially so as the Tabloid was quickly to become more of a hack than a hacker down of Zeppelins, or anything so fierce.

Sopwith Baby http://pilots-n-planes-ww1.com

And here it may be emphasized that the later 'improved' Schneider, officially called the Baby and will be described under that name, continued to be loosely referred to as a 'Schneider'; and as J. M. Bruce recorded plaintively in his British Aeroplanes 1914-18 'There is much confusion in most of the records of the exploits of both types.'

Sopwith Baby

Sopwith Baby http://pilots-n-planes-ww1.com

Sopwith Baby Sopwith Aviation Co. by Bob Pearson http://www.internetmodeler.com

Sopwith Baby, 3View download a 1000pixel image

For more about the Sopwith Sopwith Baby see ...

Bruce, J.M., Sopwith Baby, Datafile #60 The Sopwith Baby has long been a favorite for me among First World War aircraft. Its clean, rectilinear lines contrast and compliment the sizeable, blocky floats of its landing gear. Datafile #60 is the first publication dedicated to describing this aircraft. The title of this volume should probably read "Sopwith Schneider/Baby", for indeed the Baby was a development of the successful 1914 Schneider Trophy winner, a modified Sopwith Tabloid. The Sopwith racing floatplane handily won the contest with an average speed of 86.6 mph with a malfunctioning Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine. This victory bestowed the design with a name as the Sopwith Schneider. With the outbreak of the war in the summer of 1914, there was considerable concern in Britain for bombing attacks by German Zeppelins against the Royal Navy. The strategy developed to counter this real threat was to embark aircraft aboard ships in order that this menace could be countered as far from potential targets as possible. The availability of a nimble, swift single-seat Seaplane in the Schneider made it the obvious choice for the Royal Navy's first ship-borne fighter aircraft. Early operational uses of the Schneider were fraught with problems, particularly weakness in float construction resulting in the loss of several aircraft operationally. There were also problems with providing these machines with effective armament. Initially, the Sopwith floatplanes carried Ranken Darts (special, hand-launched incendiary bombs designed to pierce a Zeppelin's covering and burst inside the gas cells) and grenades. Lewis machine guns were also used, but these were never effectively synchronized to fire through the propeller of this (or any other) aircraft, and were never well employed on these machines. With the added weight of armament the Schneider came a decrease in its overall performance. The development of the Baby design, with a more powerful engine and redesigned wings, was an attempt to improve this fighter design's performance and enable it to compete with newer designs of the enemy. While a number of innovative developments were tried, including full span flaps to improve lift, the pace of these improvements was slow. Sopwith Babies were in production almost until the end of the war, well after it had essentially become an obsolete aircraft. Jack Bruce makes another excellent contribution to the Albatros Datafile series with this well-written and concise text and its wealth of photographs. Indeed, this volume is one of the larger books in the Datafile series, even though it covers only the basic Sopwith designs (Blackburn, Fairey, and the Italian license builder Ansaldo all produced variations on the basic design). Series editor Ray Rimell promises that these sub-types will be the focus of a future publication. This monograph is an excellent addition to the enthusiast's library and an invaluable reference for the modeler. Highly recommended.

|

© Copyright 1999-2002 CTIE - All Rights Reserved - Caution |

C. Howard Pixton

C. Howard Pixton