Louis Pierre Mouillard (1834 - 1897)

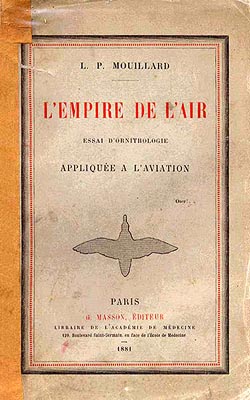

In 1881, Louis Mouillard wrote L'Empire de l'Air (Empire of the Air), in which he proposed fixed-wing gliders with cambered bird-like wings. He also proposed that aviators master gliding to gain the skills needed to pilot an aircraft. He had been experimenting with gliders since 1856, and although his own gliders were unsuccessful, he realized the importance of gliding to the future of aviation-a perspective that was later shared by Otto Lilienthal.

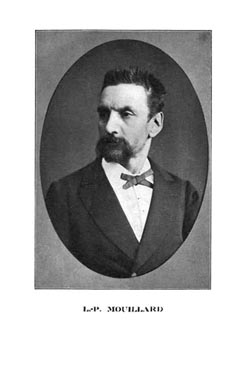

Louis Mouillard Louis Pierre Mouillard was an inspiration to many who engaged in aerial pursuits in the last part of the 19th Century. His most well-known book, L'Empire de L'Air, was published in France in 1881 and soon became a widely recognized classic. It was reprinted by the Smithsonian Institution in English in 1893 as The Empire Of The Air.

"L'Empire de l'Air" (Empire of the Air), 1881 Download a 500pixel image

Mouillard carried on a correspondence with Octave Chanute and ...regarding aluminum, Mouillard observed "It is the metal for aviation" (July 21, 1891). Later he stated that he had "...the facility of vision, the rocket is always the engine, the propellant" (March 10, 1894).

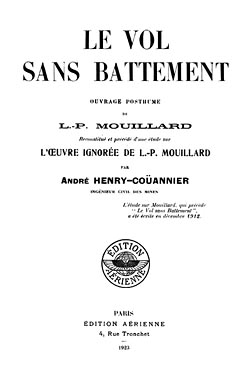

Progress in Flying Machines "Le vol sans battements" "...M. Mouillard gives but a scanty description of his experiments with this aeroplane in "L'Empire de l'Air," so little, indeed, as to suggest further inquiry; but he has since written another book, which he entitles "Le vol sans battements" (flight without flapping), which is now nearly ready for the press, and wherein he records further observations, explains more fully his ideas and the results of his meditations, giving freely, as he expresses it, "all that he knows" and in which there is a fuller account of the experiment in question."

"Le Vol sans Battements" (Flight without Flapping), frontspiece portrait Download a 500pixel image

"Le Vol sans Battements" (Flight without Flapping) Download a 500pixel image

Pilot vs Chauffeur 1881 - Louis Mouillard, France, writes another milestone in aeronautics, Empire of the Air, in which he proposes fixed-wing gliders with cambered wings, like birds. He also proposes that aviators practice in gliders to gain the skill needed to pilot an aircraft in the air. Up until that time, everyone in the infant field of aviation presumed you could navigate the sky with no more skill than a chauffeur. It split the field into two camps, each with a different approach to making a practical aircraft. The chauffeurs focus on engineering, making a powered flying machine. The pilots practice with gliders to gain skill before attempting powered flight.

Progress in Flying Machines While almost all inventors and experimenters of aeroplanes have proposed some sort of motive power, and have found their designs paralyzed very soon by the want of a sufficiently light motor, there have been at various times, as already intimated, keen observers of the flight of soaring birds, who have held that once under way in a sufficient breeze, the performance involves no muscular movement whatever, save in balancing, and that the wind alone furnishes sufficient motive power (if blowing from lo to 30 miles per hour) to enable man to soar and to translate himself at will in any direction even (paradoxical as it may seem) against the wind itself.

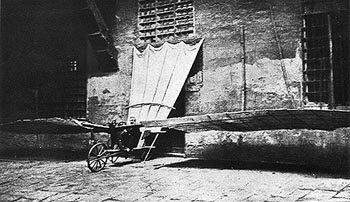

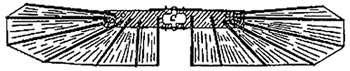

Mouillard's Glider #4, Cairo, Egypt, 1878 Chief among these observers in recent days stands M. Mouillard, of Cairo, Egypt, who has spent over 30 years in watching birds soar in tropical latitudes, and who published, in 1881 a very remarkable book (in French), "L'Empire de l' air," which should be read by all those seriously interested in the solution of the problem of flight. This book, the result, as the author explains, of a passionate, vocation which began at the age of 15 is almost wholly a record of personal observations and deductions. Its sub-title designates it as an "essay upon ornithology as relating to flight," but it is far more than that, for it not only describes the flight and manoeuvres of birds, and gives good reasons for the author's belief that they can be imitated by man, but it describes four attempts which he has made to do 50 with various forms of apparatus. M. Mouillard underrates, perhaps, the value of mathematical investigation, and he sometimes errs in his explanation of physical phenomena; but his observations are unrivaled, and they are presented with a particularity of circumstance, a vivacity and a charm which photograph them at once on the mind of the reader. He begins by explaining the difference between useful and unfruitful observations of creatures so willful, so swift, and so shy as the birds; then he describes the various modes of flight (both rowing and sailing), and the movements of the various organs, such as the wings and the tail; the influence of their shape in determining the mode of progression and the speed of the various species, and he shows conclusively that if these organs are properly shaped therefor, the heavier the bird the more perfectly he soars, and can, once initial speed is gained, sail indefinitely upon the wind without further flapping his wings This is the keynote of the book; observation after observation is described, anecdote after anecdote is related, to impress upon the reader that there need be no flapping whatever, if only the wind be strong enough; and that when there is no wind, the soaring bird must come down to the ground or resort to flapping, like the rowing birds. Then the effect of the speed of the wind is discussed. It is shown that certain species of soaring birds with broad wings, such as the kites, the eagles, and the vultures can sail upon a wind blowing at 10 to 25 miles per hour, but must seek shelter when it increases to a gale, while the sea-birds, with long and narrow wings, such as the gulls, the frigate bird, the albatross, sport indefinitely in the tempest blowing at 50 or more miles per hour. He arrives at the conclusion that when man succeeds in imitating the manoeuvres of the soaring birds, he will utilize the moderate winds, and attain to speeds of about 25 to 37 miles per hour. M. Mouillard also passes in review the individual mode of flight and characteristics of the various species of birds, both the rowers and the sailers; comprising some 13 different types, and giving tables from his own measurements of weights, surfaces, dimensions, etc., which have been compiled by M. Drzcwiecki, and have already been quoted by the writer under the head of "Wings and Parachutes;" while he finally expresses a strong opinion that the easiest type for man to imitate is the great tawny vulture of Africa (Gyps fulvus), which weighs some 16.50 lbs., and spreads some 11 sq. ft. of surface to the breeze. M. Mouillard explains how, in his opinion, the manoeuvres of this bird can be imitated, so as to obtain both a sustaining and a propelling effect from the wind, and he describes (much too briefly) the four several attempts which he had then made to demonstrate the correctness of his theory of the possible soaring flight of an aeroplane for man. The third of these aeroplanes, as described in 1881, is shown in fig. 61. It consisted of two thin boards, properly stiffened, to which were attached ribs of "agave" wood (an African aloe, exceedingly light and strong), which ribs carried the fabric constituting the two wings. The two boards were hinged vertically together (somewhat imperfectly) at the center, and the operator stood upright in the central space at c, suspended by four straps attached to the boards near the hinge; two of these straps passing over the shoulders and two between the legs. Moreover, light wooden rods extended from the feet to the outer ends of the boards, so that the angle of the wings with each other could be varied at pleasure. Standing upright, with this apparatus strapped on, the hinge was about at the height of the pit of the stomach, the arms being extended out flat upon the boards, and slipping under straps; M. Mouillard trusting to such shifting of his body within the space c as he could effect by resting his weight on his arms, to produce the necessary changes in the center of gravity of the apparatus, which were required by the changes in the angles of incidence. The whole apparatus weighed 33 lbs., but was found unduly light, as the parts yielded and the wood cracked when tested with vigorous thrusts of the legs. It had been hastily constructed, with such materials as the country afforded, and the builder was not satisfied with it. M. Mouillard gives but a scanty description of his experiments with this aeroplane in "L'Empire de l'Air," so little, indeed, as to suggest further inquiry; but he has since written another book, which he entitles "Le vol sans battements" (flight without flapping), which is now nearly ready for the press, and wherein he records further observations, explains more fully his ideas and the results of his meditations, giving freely, as he expresses it, "all that he knows" and in which there is a fuller account of the experiment in question. From this forthcoming book M. Mouillard has kindly furnished the following extract concerning the experiment with the apparatus shown in fig. 61.

It was in my callow days, and on my farm in the plain of Mitidja, in Algeria, that I experimented with my apparatus, No. 3, the light, imperfect one, the one which I carried about like a feather.

fig. 61: Mouillard, 1865 Then M. Mouillard repaired the injured aeroplane, and he tried it again a few days later. Of this later experiment he says in "L'Empire de l'Air":

I had no confidence, as I have already stated, in the strength of my aeroplane. A violent wind gust came; it picked me up; I became alarmed, did not resist, and allowed myself to be upset. I had one shoulder sprained by the pressure of the two wings, which folded up against each other like those of a butterfly when at rest.M. Mouillard then determined to make no more experiments with this incomplete machine, but to build a better one, with which he could control all the manoeuvres necessary for soaring, but shortly afterward his circumstances led him to leave the farm and to remove from Algeria to Cairo, Egypt. Here, in a great city, he no longer had the facilities for experimenting that he possessed on the farm, for he had to go out some distance to secure space and privacy for each experiment. Then came illness; the former gymnast became a cripple, so that he could no longer perform for himself the acrobatic manoeuvres necessary to experiment with a soaring apparatus, but still he persevered, and he describes in "L'Empire de L'Air" the design for the fourth apparatus, of which he began the construction in 1878, but which was interrupted by ill-health. Since the publication of his book in 1881 M. Mouillard is understood to have been continuously engaged in perfecting and simplifying his proposed soaring apparatus, and in trying experiments (by proxy) with models on a small scale. He says that he will soon be prepared to have the matter tested on a large scale, and that he has never wavered from absolute conviction in the truth of the principles which he laid down in "L'Empire de l'Air," in which he expresses himself as follows:

I hold that in the flight of the soaring birds (the vultures, the eagles, and other birds which fly without flapping) ascension is produced by the skillful use of the force of the wind, and the steering, in any direction, is the result of skillful manoeuvres so that by a moderate wind a man can, with an aeroplane unprovided with any motor whatever rise up into the air and directed himself al will, even against the wind itself.M. Mouillard then continues:

It will doubtless be very difficult for many persons to admit that a bird can with a moderate wind, remain a whole day in the air with no expenditure of power. They will endeavor to suppose some undetermined pressures or some unseen flappings. In point of fact, the human understanding does not readily admit the above truth; it is astonished, and seeks for all the evasions it can find. All those who have not seen say, when ascension without expenditure of force is mentioned to them, "Oh, well, there were some motions which escaped your observation. "Whoever has seen a boy's kite ascend into the air, and considered that the string may be replaced by a weight, if only the equilibrium be secured and maintained, will have no difficulty in granting the correctness of M. Mouillard's assertion that the power of the wind is quite sufficient to secure ascension, but it will not so readily be understood how it is also sufficient to secure progression even against the wind. It will, indeed, be conceived that an aeroplane possessed of initial velocity can soar in a circle in the wind like a bird, and by changing its angle of incidence, descend somewhat when going with the wind. and rise again in consequence of the greater "lift" when facing the wind, thus gaining in height at every lap, and eventually utilizing the elevation thus gained in gliding in any desired direction, always provided that the equilibrium be maintained but this involves very delicate manoeuvres, which will be further considered when we come to sum up the results of all the experiments with soaring devices, and indeed the subject warrants a paper by itself which may be placed in an appendix.

Means for Aerial FlightUnited States Patent #582,757 : 1897-05-18Mouillard, Louis Pierre, Cairo, Egypt, England

Mouillard Patent of 1897, p.1 Click to enlarge

Mouillard Patent of 1897, p.2 Click to enlarge

Mouillard Patent of 1897, p.3 Click to enlarge

Mouillard Patent of 1897, p.4 Click to enlarge

It may, however, be said here that the French aviators., after having long doubted the reality of the performance of sailing flight by the birds, whose evolutions they were unable to watch in their climate, have had so many corroborations furnished to them by trustworthy witnesses, that they now generally admit that a soaring bird can sustain himself indefinitely on a wind, without flapping, and that man may learn to imitate him if only a proper apparatus be designed, and the operator possesses the necessary knowledge and skill to work it, so as to perform the right manoeuvres and at the right time.

What Mouillard Did Until a few months ago the name of Louis Pierre Mouillard was known to only a few deep students of aeronautics and to them he appeared as an elusive personality, a French student -- farmer -- poet -- who had lived in Egypt and had written a remarkable book upon bird flight. Of his life and the value of his work nothing definite was known. Two years ago, during the Heliopolis meet, somebody remembered that Mouillard had lived and died at Cairo and started an investigation, which ended with the finding of a boxful of papers of Mouillard in the cellars of the French Consulate, where they had been stored on the death of Mouillard....more

The Chanute - Mouillard Correspondence Being the letters exchanged between Octave Chanute, American engineer, and Louis-Pierre Mouillard, French author and student of bird flight, mainly on the subject of aeronautics....more

|

© Copyright 1999-2002 CTIE - All Rights Reserved - Caution |