John William Dunne (1875-1949)

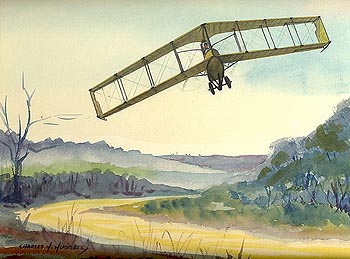

A Burgess-Dunne with pilot Clifford Webster, and its owner, circa 1915. http://adrageous.com/burgessdunne/listings/25.html

The owner a New York doctor had purchased the plane to fly into the remote Adirondack lake country to make summer house calls on his wealthy patients. The story goes that the Doc returned the plane to the factory for routine maintenance after flying it for quite some time. The factory then proceeded to make some changes to the cockpit controls without telling the doc. He soon discovered after take off that something was drastically wrong. They had deliberately REVERSED the left and right aileron controls to correct a design defect so that the plane couldn't accidentally drop a wing into the water when banking into a turn. The good doctor nearly crashed before figuring this out. The U.S. Navy ordered six of these but most were destroyed in a fire at the factory before delivery.

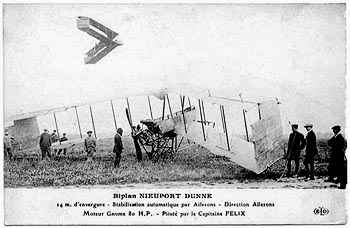

Burgess-Dunne of 1914

Burgess-Dunne #2 was bought by the Canadian Army and was Canada's first military aircraft. The aircraft was flown by Clifford Webster to Quebec City where it was loaded onto a ship for the Atlantic crossing, but never made it intact. The ship encountered rough seas and the plane which was simply lashed to the deck and left completely assembled was destroyed.

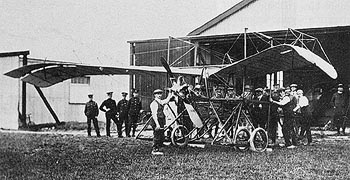

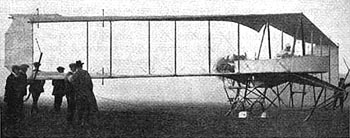

He actually built two test aircraft. Later, a Dunne appeared in a static display at the Paris Air Show in 1915. Right: Believed to be a photo of J.W. Dunne in one his craft

After Burgess acquired the rights to the Dunne aircraft design, he quickly learned that the plane was a very stable flying machine but it wanted to fly directly into the wind. It was very sensitive to cross winds and even a 10 degree off heading breeze could make for a tricky landing. It was therefore decided to make it into a sea plane so cross winds could not affect it's landing path.

Barry MacKeracher's Burgess-Dunne Replica

Don Eatherley writes in his essay on MacKeracher... The original Burgess-Dunne had a brief career with the Canadian Army. After war was declared with Germany in August 1914, the Canadian Army decided it needed an aircraft to fly photoreconnaissance and artillery spotting in support of ground troops going to Europe.

Barry MacKeracher's Burgess-Dunne Replica (detail)

A test version of a floatplane designed by Englishman J.W. Dunne and constructed by American boat-builder Stirling Burgess was acquired for $5000 and loaded onto the S.S. Athenia for the trip to England. However, the plane was so badly damaged in transit, that it was no longer flyable. The Burgess-Dunne's wing span was 47 feet and length was 26 feet from nose to rear floats on the wingtips. It was 11 feet, 6 inches high and had a single float mounted directly under the pilot and passenger seats. Normal cruising speed ranged from 60 to 65 miles per hour.

Don Eatherley

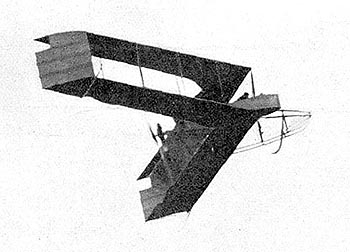

William J. Claxton http://www.blackmask.com About the time that M. Bleriot was developing his monoplane, and Santos Dumont was astonishing the world with his flying feats at Bagatelle, a young army officer was at work far away in a secluded part of the Scottish Highlands on the model of an aeroplane. This young man was Lieutenant J. W. Dunne, and his name has since been on everyone's lips wherever aviation is discussed. Much of Lieutenant Dunne's early experimental work was done on the Duke of Atholl's estate, and the story goes that such great secrecy was observed that "the tenants were enrolled as a sort of bodyguard to prevent unauthorized persons from entering". For some time the War Office helped the inventor with money, for the numerous tests and trials necessary in almost every invention before satisfactory results are achieved are very costly. Probably the inventor did not make sufficiently rapid progress with his novel craft, for he lost the financial help and goodwill of the Government for a time; but he plodded on, and at length his plans were sufficiently advanced for him to carry on his work openly. It must be borne in mind that at the time Dunne first took up the study of aviation no one had flown in Europe, and he could therefore receive but little help from the results achieved by other pilots and constructors. But in the autumn of 1913 Lieutenant Dunne's novel aeroplane was the talk of both Europe and America. Innumerable trials had been made in the remote flying ground at Eastchurch, Isle of Sheppey, and the machine became so far advanced that it made a cross-Channel flight from Eastchurch to Paris. It remained in France for some time, and Commander Felix, of the French Army, made many excellent flights in it. Unfortunately, however, when flying near Deauville, engine trouble compelled the officer to descend; but in making a landing in a very small field, not much larger than a tennis-court, several struts of the machine were damaged. It was at once seen that the aeroplane could not possibly be flown until it had been repaired and thoroughly overhauled. To do this would take several days, especially as there were no facilities for repairing the craft near by, and to prevent anyone from making a careful examination of the aeroplane, and so discovering the secret features which had been so jealously guarded, the machine was smashed up after the engine had been removed. At that time this was the only Dunne aeroplane in existence, but of course the plans were in the possession of the inventor, and it was an easy task to make a second machine from the same model. Two more machines were put in hand at Hendon, and a third at Eastchurch. On 18th October, 1913, the Dunne aeroplane made its first public appearance at Hendon, in the London aerodrome, piloted by Commander Felix. The most striking distinction between this and other biplanes is that its wings or planes, instead of reaching from side to side of the engine, stretch back in the form of the letter V, with the point of the V to the front. These wings extend so far to the rear that there is no need of a tail to the machine, and the elevating plane in front can also be dispensed with. This curious and unique design in aeroplane construction was decided upon by Lieutenant Dunne after a prolonged observation at close quarters of different birds in flight, and the inventor claims for his aeroplane that it is practically uncapsizable. Perhaps, however, this is too much to claim for any heavier-than-air machine; but at all events the new design certainly appears to give greater stability, and it is to be hoped that by this and other devices the progress of aviation will not in the future be so deeply tinged with tragedy.

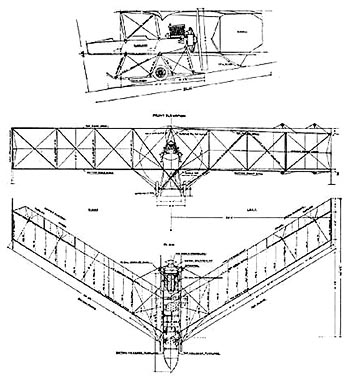

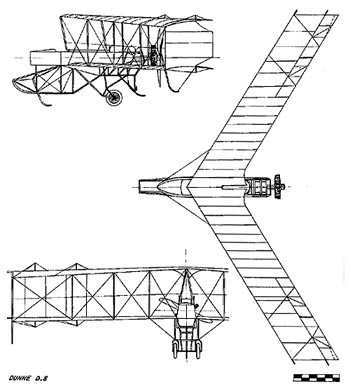

Dunne D1, Glen Tilt, Scotland, 1907

Dunne D2, 3view

Dunne D4, Blair Atholl, Perthshire, Scotland, 1908

At about the same time John William Dunne was also present at Farnborough, producing a series of 'powered gliders', the most successful of which was the D4 which flew under its own power for 120ft on 10th December 1908 at Blair Atholl, Perthshire. Dunne's main contribution to aviation was in the field of stability which the Wright/Cody designs lacked. http://www.natdems.org.uk/v50t1.htm

Dunne 5, 3view

Dunne D5, 2view

Munson, Kenneth, Pioneer Aircraft 1903-1914

Dunne D.5, March 11, 1910: World's first swept-wing. Unusually stable, even at very low speeds, this and the later monoplane version (D6) will help stimulate ideas some thirty years later. Designed by John W. Dunne and built by Eustace, Oswald and Horace Short.

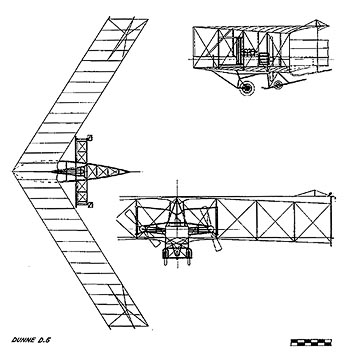

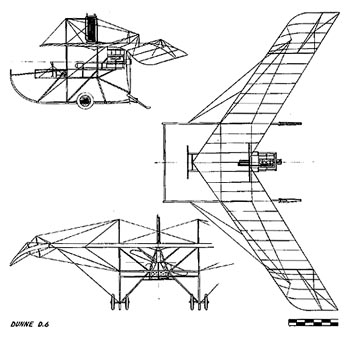

Dunne D6, 1911 Download a 1000pixel image http://www.alexander-schleicher.de

Dunne D6, 1911 Flight Magazine

Dunne D6, 3view

Dunne D8 Download a 1000pixel image http://www.alexander-schleicher.de

Dunne D8, 80hp Gnome Royal Aero Club

Dunne D8 C.F. Andrews

Dunne D8, 50hp Gnome C.F. Andrews

Dunne D8, 3view

Dunne D8, 2view

Munson, Kenneth, Pioneer Aircraft 1903-1914

Dunne d8

Dunne D8

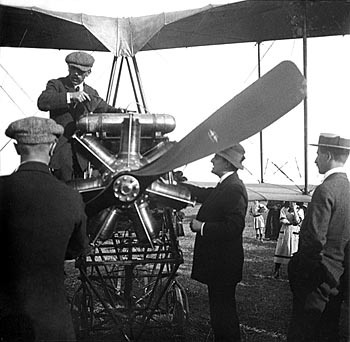

Dunne D8, engine detail, 1910 Photo by Augustin Seguin (1898-1964) Download a 750pixel image

This and the following Dunne D8 image come from an outstanding 3D website which features stereo images by Augustin Seguin (1898-1964), pilot, engineer, and amateur photographer. They have been processed as Anaglyphs (a Red/Blue composite) but, as here, are also available as mono images. The term Anaglyph is derived from two Greek words meaning "again" and "sculpture". The conventional method of viewing stereoscopic photographs in the last century was to use a viewer which held a pair of images, and which enabled each eye to see only one; by fusing these together a three dimensional effect was recreated. The discovery of anaglyphic 3-D has been attributed to a French gentleman named Joseph D'Almeida, who used the technique in the 1850s to project glass stereo lantern slides. William Friese-Greene created the first three-dimensional anaglyphic motion pictures in 1889, which had public exhibition in 1893. [www.bbc.co.uk]

Dunne D8, engine detail, 1910 Photo by Augustin Seguin (1898-1964) Download a 750pixel image

Dunne D8, 1910 Charles Hubbell Download a 750pixel image

Nieuport-Dunne, c.1910 Download a 1000pixel image [170kb]

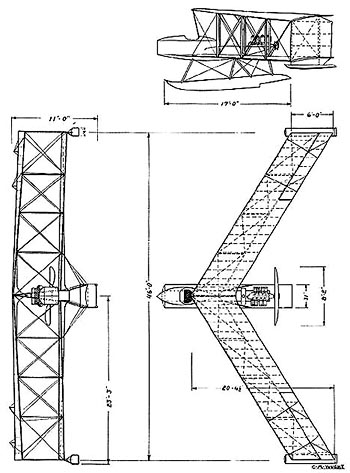

Burgess-Dunne 3, 1910, 3view

Burgess-Dunne 3 of 1910, 2view Munson, Kenneth, Pioneer Aircraft 1903-1914, Blandford Press, 1969

Burgess-Dunne of 1914 http://www.airforce.dnd.ca/equip/burgdunnelst_e.htm

This swept-wing, tailless seaplane of the Canadian Aviation Corps was the first Canadian military Aircraft having been bought for the newly formed (16 September, 1914) first military aviation service in Canada. As no Aircraft were available in Canada at the time, the newly appointed commander of the CAC, E.L. Janney, journeyed to Massachusettes, immediatley closed a deal for the purchase of the Aircraft, and had it shipped to Lake Champlain where an American pilot was ready to ferry it to Canada as Janney was not a qualified pilot. The Burgess-Dunne left Lake Champlain for Quebec City , Quebec where it arrived on 29 September after several delays and was shipped overseas on 30 September on board the S.S. Athenia.

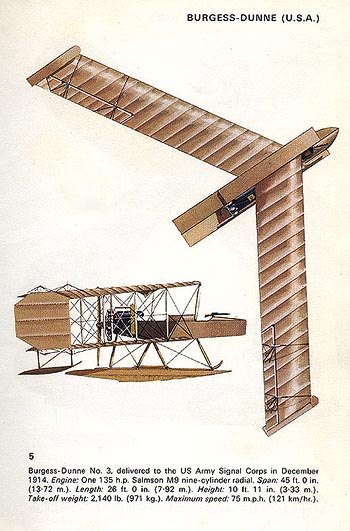

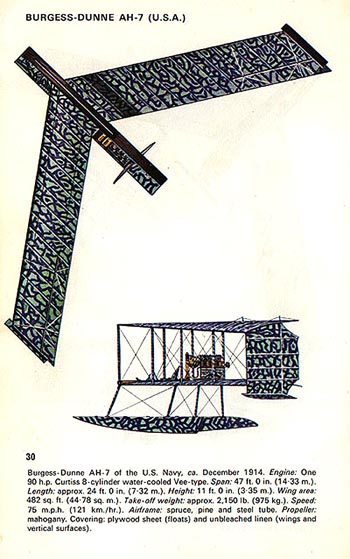

Burgess-Dunne AH-7 of 1914 Munson, Kenneth, Pioneer Aircraft 1903-1914, Blandford Press, 1969

Many of the above images came from the pages by David 'Dannysoar' Dodge More than you want to know about Dunnes. On this site they have been re-collated and as needs be re-named with other images to create a developmental timeline. This is a work in progress and will be added to as further images are collected.

"...At about the same time John William Dunne (1875-1949) was also present at Farnborough, producing a series of 'powered gliders', the most successful of which was the D4 which flew under its own power for 120ft on 10th December 1908 at Blair Atholl, Perthshire. Dunne's main contribution to aviation was in the field of stability which the Wright/Cody designs lacked."

http://www.rcafmuseum.on.ca/Burgess_Dunne.htm By Col. R.D. Russell (Ret'd) and Ms. Jodi Eskritt, Curator RCAF Memorial Museum. Military aviation was truly in its infancy when First World War began in August 1914. Britain's Royal Flying Corps consisted of a total of sixty-three assorted unarmed aircraft, operating from an improvised airfield outside of Amiens, France. From there they patrolled the lines and reported on enemy troop concentrations, which could not be seen from ground level, acting as "airborne cavalry units" and providing a new instrument of military intelligence for the commanding Generals. At that time the roles of air fighting, bombing and ground attack had not even been visualized.

Burgess-Dunne of 1914 http://aviart.tcel.com/dunne.htm Download a 750 pixel image Several far-sighted Canadians had begun to work towards the creation of a Canadian air force as early as 1908. Among these would be a number of civilian aviation pioneers including the members of the Aerial Experiment Association (Silver Dart and Baddeck trials), and military staff officers. Colonel Eugene Fiset, Deputy Minister, Colonel R.W. Rutherford, Master of Ordnance and Major G.S. Maunsell, Director of Engineering. However, despite years of carefully laying the groundwork, the creation of Canada's first air force would fall to three other men. The real birth of Canadian military aviation can be dated to early September 1914 when W.F.N. Sharpe and E.L. Janney paid Sir Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia and Defence, a visit at Valcartier where he was preparing the First Canadian Expeditionary Force for embarkation for Europe in October. By the 16th September Hughes had appointed Janney as a " provisional commander", commissioned him in the rank of Captain, and authorized him to look for an aircraft in the United States, since construction facilities were non-existent in Canada. Taking his cue from Hughes' emphasis on the words "quick delivery", Janney had already made one visit to the United States (around 12th September) and made his selection for the Canadian Aviation Corps' first aircraft. On the day of his appointment he crossed the border once again - with pistol on hip, appointment in pocket and a government cheque for $5,000. Janney returned to the Burgess Company of Marblehead Massachusetts on the 17th and purchased their well-used, demonstration model Burgess-Dunne two-seater tailless swept-wing pusher floatplane (designed by British aeronautical pioneer Lieutenant J.W. Dunne and built by American boat builder Stirling Burgess). After rushing an overhaul, Janney and Webster [the company pilot] set off for Valcartier, Quebec. This flight was an adventure in itself, with a forced landing about one hour after take-off which resulted in them being held temporarily as suspected enemy agents, and another one just outside Champlain where a passing motorboat noted their distress and they were towed in. Eventually, the Burgess-Dunne arrived at Quebec City where it and the Canadian Aviation Corps, now consisting of two officers and one mechanic (Sharpe had enlisted Harry A. Farr from a Victoria infantry unit in Janney's absence), were put aboard a troop transport taking the Canadian Expeditionary Force to Britain. The aircraft was literally tied to the deck, and bounced all the way across the Atlantic. Having formed the CAC Hughes characteristically lost all interest in it, and gave it no further support. Hughes further neglected to inform the Headquarters or the 1st Contingent of the CAC formation and they were uncertain as to how to employ them. Janney was determined to create a proper aviation corps and once in the United Kingdom set out on an inspection tour with the intention of forming a one-flight squadron (estimated cost $116-117,000). Militia Headquarters quickly informed the 1st Contingent `to sever Lieutenant [sic] Janney's connection with the CEF.' On the 23 January 1915, Janney was struck off strength and sailed for Canada. He would make two more brief appearances in Canadian aviation history: the first as Sub-Lieutenant E.L. Janney of the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve and the second (unconfirmed) as an aerobatics pilot after the war. Following its initial flight, the Burgess-Dunne aircraft never took to the air again. It was left standing, damaged in transit, on the docks until the request was made to move it. Eventually it appears to have been shipped to the Central Flying School at Upavon where it disappears from the record. An investigation several months later would discover only a few parts that couldn't even be sold for scrap and two inner tubes which had been left at a local pub. An ignoble end for an aircraft of unique and, for the day, advanced design. The other officer, Lieutenant W.F.N. Sharpe was first trained as an observer with the Royal Flying Corps then returned to England for pilot training. On his first solo flight, he became the first Canadian service aviation casualty when he was killed in a flying accident on February 4, 1915. The mechanic, H.A. Farr was discharged from the CEF in May 1915 `in consequence of Flying Corps being disbanded.' From that time on, until the end of 1916, military service entry for anyone who wished to be an aviator was controlled by individuals in Ottawa who, in addition to their other duties, acted for this purpose on behalf of the RFC and the RNAS. A total of 22,811 Canadians served and 1,563 gave their lives. They flew operationally in every area, from Archangel to East Africa. They did not, however, fly as members of a Canadian Air Force but served with the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service components of the British Forces. In 1918, when it was decided to amalgamate the various British formations into the Royal Air Force, almost a third who put on the new "light blues" were Canadian. Soon, however, growing pride and nationalism, aroused by Canadian military accomplishments on the battlefields, at sea and in the air brought forth a call for a distinctly Canadian army, navy and air force. As a result, on August 5, 1918, the Canadian Air Force was created with No. 1 and No. 2 Squadrons forming in England. On February 15, 1923, King George V approved the designation Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and on April 1, 1924 the RCAF became a permanent component of the Department of National Defence on an equal basis with the Army and the Navy. Ten pilots were among the top 26 leading Allied "Aces" - all credited with 30 or more kills. Heading this list was Major W.A. (Billy) Bishop, with 72 victories. Another Canadian, Major Raymond Collishaw, was second with 60 victories. When the war ended, more Canadians were proficient in the new art of flight, in proportion to the total population, than were the citizens of any other Allied country - and it all started with a $5000, second-hand, Burgess - Dunne floatplane.

http://mars.ark.com/~camuseum/RCAF/part1.html On 16 September 1914 (while the original Canadian Expeditionary Force was forming up in Valcartier), Col Sam Hughes, Minister for the Militia and Defence, authorized the creation of the Canadian Aviation Corps (CAC). This corps was to consist of one mechanic and two officers. E.L. Janney of Galt, Ontario, was appointed as the "Provisional Commander of the CAC" with the rank of Captain. The expenditure of an amount not to exceed five thousand dollars for the purchase of a suitable airplane was approved. The aircraft selected was a float-equipped Burgess-Dunne bi-plane from the Burgess Aviation Company of Massachusetts. Capt Janney flew the aircraft back to Canada. Upon his arrival in Sorel, Quebec, Capt Janney was arrested by Canada Customs and the aircraft was impounded. After Canada Customs received notification from the Department of the Militia and Defence, Capt Janney and the aircraft were released. As it turned out, this was to be the only flight of Canada's first military aircraft.

http://www.c-and-e-museum.org/chap3_e1.htm On 16 September 1914 Sir Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia and Defence, ordered the formation of the Canadian Aviation Corps. This first attempt to form a Canadian air force ended in a fiasco. The corps acquired a commander, one other officer and a Burgess-Dunne aeroplane. It deployed to Salisbury Plain as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The aeroplane disintegrated in the damp winter of 1914-15, the commanding officer resigned his commission and the other member transferred to the Royal Flying Corps where he died in an accident on 4 February 1915.

http://mars.ark.com/~camuseum/RCAF/part1.html While Capt Janney was accepting Canada's first military aircraft, the other two members of the CAC were recruited: Lieutenant W.F.N. Sharpe of Prescott, Ontario, and Staff Sergeant H.A. Farr of West Vancouver, British Columbia. Immediately after Capt Janney and the Burgess-Dunne were released from Customs, the aircraft was crated for shipping, and the CAC sailed on the S.S. Athena with the First Canadian Contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. After landing at Plymouth, England, the aircraft was off-loaded and shipped to Salisbury Plain were it was considered unsuitable for military service. It was placed in storage, where it eventually rotted and was written off. Capt Janney, now without an aircraft, resigned his commission and returned to Canada. Lt Sharpe continued in England with the Royal Flying Corps. He was killed while on a solo flight in a Maurice Farman bi-plane on 4 February 1915. This ended the first attempt at a national air force.

http://data4.archives.ca

King George V authorized the Canadian Air Force (CAF) to be redesignated as the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) effective in 1924, but the history of Canada's military in the air began even earlier... When Canadian troops left for Europe on September 30, 1914, they were accompanied by a Burgess-Dunne seaplane - the country's first military aircraft. Canada Post Corporation, Canada's Stamp Details, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1999, p. 21-23.

http://www.rcaf.com/archives/burguss_lemon/index.html The first direct attempt to interest Canada's military men in aircraft had been a dismal failure. In August 1909 Baldwin and J.A.D. McCurdy had attempted to demonstrate the capabilities of their two biplanes, Silver Dart and Baddeck No. 1, to a picked group of officers at Petawawa. A few successful flights had indeed been made, but both aircraft were quickly wrecked. The trouble lay largely with the unsuitable terrain the Army had supplied as a flying-field: it was rough, uneven, and dotted with bushes.

The Burgess-Dunne of the Canadian Aviation Corps at Quebec City http://www.rcaf.com/archives/burguss_lemon/index.html

Of course, in those days, very few people outside the little circles of flying enthusiasts had any conception of the operating requirements and limitations of aircraft. In view of the general apathy of military men toward aviation at that time, it was a bit surprising to find that Canada's Minister of Militia and Defence, Col. Sam Hughes, authorized the formation of an air arm only a few weeks after the out-break of the First World War. The first reference to this peculiar body in official files is an order initialed by "S.H." dated 16 September 1914, appointing one E.L. Janney as Provisional Commander of the "Canadian Aviation Corps", with the rank of Captain, and authorizing him to buy for the Corps "one biplane" for a price not to exceed $5000. As far as any records indicate, Janney had never flown, even as a passenger, and knew next to nothing about aircraft. The new "Provisional Commander" strapped an impressive revolver around his. waist and sashayed off to the US of A in search of a flying machine he might buy, such equipment being then, in Canada, about as rare as a great auk. He later claimed to have visited several manufacturers of aircraft in the eastern US before striking a deal with the Burgess company of Marblehead, Massachusetts. This was a ship building concern which branched out into production of "Burgess Aeroplanes" in partnership with one Greely S. Curtis of Salem, Mass. According to Frank H. Ellis, the aircraft in question was the first produced by this company. Even for that date, when nearly all flying machines were designed "by guess and by God", the Burgess machine was outstandingly different. A tailless craft with swept-back wings, it was designed in 1907 by Lieut. J.W. Dunne, a brilliant British engineer and metaphysicist. He had apparently developed his basic plan for the type from study of the flight characteristics of the seed of the Zanonia macroparpa plant. The Burgess company had bought from Dunne the rights to build his aircraft under license. Like the earlier gliders Dunne had built on the same plan, the Burgess derivative was inherently stable. My library includes a letter from Clifford L. Webster, the pilot who flew the craft to Canada, in which he comments, "The plane was so stable that anyone could fly it at a reasonable altitude." It was so stable, in fact, that it would have been of little use for pilot training, giving students a false and dangerous impression of the handling characteristics of aircraft in general. The aircraft had a wingspan of forty feet, a nacelle seating the pilot forward and his passenger aft, and a pusher propeller geared to a Curtiss engine of a claimed 100 hp. (This had been obtained from Clenn Curtiss-not Greely S. Curtis). When demonstrated to Janney, the craft was mounted on a single, central float. it was controlled in flight by a lever on each side of the pilot, which activated clevons at the wingtips. When moved together in the same sense, these levers caused the clevons to function as elevators; when moved in opposite directions, they caused these surfaces to act as ailerons. This was another feature which made the Dunne unsuitable for use as a military aircraft-apart from the Wright brothers' products, most service aircraft had by then adopted controls of the Deperdussin type. The Dunne had a top speed of some 60 mph-not out of line with the performance of the Taube, Albatros, Farinan, and Curtiss aircraft then in use. According to Pilot Webster, the Dunne could not he side- slipped. Perhaps this was partly because she had a large vertical panel spanning the gap between the wings at each itip, which were supposed to prevent inadvertent slipping; more likely it was due to the lack of any rudder. The Burgess company must have had a competent staff and good construction facilities by the standards of the day, for by the end of 1914, it had produced thirteen craft of the Dunne type. One of them, mounting a nine-cylinder Salmson engine, was accepted by the US Signal Corps and became the Army's first "warplane". When Captain Janney appeared at the Burgess plant on 17 September 1914, he was "hot to trot". The $5000 letter of credit was burning a hole in his pocket, and he had an early deadline to meet. He was due to deliver "an aeroplane" to Valcartier, Quebec, before the end of a month. Apparently the Dunne was the only aircraft he had found in his visits to various factories which was immediately available. He was in no mood to quibble, and he apparently had insufficient technical expertise to evaluate the merits and faults of the aircraft Burgess had on hand. He offered spot cash-the whole $5000 bundle-for immediate delivery. The Burgess people hesitated. They had already agreed to lease this craft, complete with pilot, for a tour the following week by a barnstorming political candidate. They were certainly considering the possibilities of further orders from the Canadian military, If this first machine aircraft was badly in need of repairs. The engine had been run "a great many hours". Both it and the airframe were overdue for maintenance chores. Nevertheless, the offer was reluctantly accepted, and the sale was concluded on 18 September. The $5000 bought the aircraft as it stood, on flotation gear, plus an undercarriage for use on land, but apparently no replacement parts were included. The agreed price was FOB Marblehead, but to cut the flying time to Quebec the company agreed to ship the machine by rail to Isle La Motte, Vermont, and to assemble it there. Further, in view of Janney's lack of flying experience, they agreed to lend their pilot, Clifford Webster, to ferry the machine from Vermont to Valcartier A letter from the Burgess company, dated 29 September 1914, includes the comment, "Mr. Burgess was not anxious to have the machine leave in such a hurry without a proper overhauling." Working at top speed company mechanics went over the engine hastily, scraping some tight connecting-rod bearings and repairing the valves. In a couple of days the craft was knocked down and bundled aboard a flat car for the run to Vermont. At Isle La Motte re-assembly was rushed, and on 21 September the aircraft finally took off for Valcartier. In 1914 any aeroplane which could repeatedly take off and land under field conditions, with fair reliability, was generally considered an adequate performer. By these standards the Burgess-Dunne was basically not a bad aeroplane, even though its speed was low and its range very limited (its fuel tank held only ten US gallons). Certainly it was very stable. In one letter from Clifford Webster, he writes, "I expect I let Janney do some of the flying before we had the engine failure," and in another he states that, on the first leg of the ferry flight, "Janney drove about a quarter of the time." Then, after a fuel stop at Sorel, they began to pay the price for the too-hurried overhaul back at the plant. Quoting again from Webster, we read, "Half an hour or so later the engine began to knock badly so I landed on the river. We decided a connecting-rod bearing had gone. Against my judgment, Janney decided we should fly on. We took off up-river into the fresh westerly wind. The engine, vibrating badly, would not give enough power to get off the ground bank, so the river being very wide there, I eased the plane round an 180 deg. turn with the wingtip pontoon barely off the water, and proceeded down-river, fighting for five feet of altitude. After about 15 minutes the engine really went bust, so I landed downwind." Soon a motor boat towed them to the shore at Deschaillons, where, in the course of beaching, two large holes were punched in the main float. Examination of the engine revealed a faulty oil pump, two seized cylinders, and several burned out bearings. As soon as they had been towed to shore Webster telegraphed to the Burgess plant for help. There is a strange lack of agreement in the various records as to how the engine problems were resolved. The files of the late Frank FIlis contain a quotation from a letter, written by some official of the Burgess company, dated 26 September 1914, but neither the writer nor the addressee is identified. This letter states as follows: "We have sent a mechanic to Canada and shipped up parts for the replacing of the connecting-rods, and two cylinders and pistons. . . . I had a phone talk with our mechanic last night, and he informs me that the running of the motor under the conditions described has burned the main bearings, and while the motor will run, it is not in good shape for continuous service. it is very evident that a new motor should be supplied for this machine at once. We could quote a price of $2750 under normal conditions, and have now raised our price $208. However, in view of the accident, which we do not believe was ours in any way, we will supply a new motor at $2500, this cutting the regular quotation. In my opinion, a new motor should be purchased 'and installed in the aeroplane at once. The old motor should be returned and thoroughly overhauled." Years later Pilot Webster wrote to Miss Marjorie Stinson giving his whole version of the flight, and he had the following to say: "We telegraphed the Burgess company, and they replied that they would have a new engine there in three days, which they did. So we removed the smashed engine, replaced an engine bed and had a couple of copper patches put an the hull. The "birdmen" started out again on 28 September, but the patches on the float leaked so badly that takeoff proved impossible. The original patches on the float were then replaced with wooden ones, which proved satisfactory when the voyage was resumed the following day. After one further overnight stop Janney and Webster decided to bypass Valcartier, as they were already long overdue. Finally, on 1 October, the weary Burgess-Dunne limped into the harbour of Quebec City, and was hastily hauled aboard the SS Athenia. By the narrowest of margins, she had become a "member" of the 1st Canadian Contingent, though she was by no means assured of overseas service. The remaining history of this orphan aircraft is rather well known in outline, though precise details are unknown to this day. it is certain that she never flew again. Fragmentary records show that she was left dismantled, completly exposed to the atrocious climate of Salisbury Plain, for many months after her arrival in England. It appears she was never again even placed under cover. Various personnel of the RFC came to glance at her from tirne to time, but all were wise enough to show no interest in her. It was all too clear that she could he of no earthly use-and none in the sky either-to any of the fighting forces, British or Canadian. Even if she had been overhauled and assembled as soon as she reached Britain, her flying life, without spare parts for maintenance, could not have stretched beyond a few hours. With her exaggerated inherent stability, her clumsy two-hand controls, and without a rudder, she was worse than useless for training fledging pilots, and had anyone even considered using her in combat, a moment's reflection would have made it clear she was no match for her potential opponents. To paraphrase Shakespeare, the fault, dear Brutus, was not in the stars-and neither was the Burgess-Dunne's destiny. The apathy of the Canadian staff officers in Britain toward this unfortunate aircraft eventually lifted enough to have them send an investigator charged with finding out what had become of the machine. The investigation was able to salvage nothing more than the inner tubes from the craft's tires.

http://www.legendinc.com Marblehead's Wright brother, W. Starling Burgess was a visionary and an inventor of the first magnitude, also becoming the largest employer in the history of the Town. The American inventor of the seaplane, he opened his Marblehead plant in 1913, after training with the Wright Brothers themselves. He produced the Burgess-Dunne flying boat, and with World War I in full swing he soon was turning out eight planes a day for the war effort with over 800 employees. On November 7, 1918 his Little Harbor plant burned to the ground, destroying all company records, and was never rebuilt. His daughter, Tasha Tudor, writes and illustrates children's books today.

http://www.aerofiles.com Dunne B-D-H, Hydro, AH-7 1914-16 = 2pOBF; 140hp Sturtevant V-8 pusher; span: 46'0" length: 24'8" (>31'0") v: 70/x/40 range: 280. John W Dunne (British patent holder) as Dunne D-10. Tailless, single pontoon, 30-degree swept-back wings, short nacelle.

Dunne B-D-H, Hydro, AH-7 (Dunne D-10) Paul Matt collection

First mounted on wheels, but after a cool reception by potential buyers, a seaplane proved to be more sellable. Army land/sea version in 1916 had 135hp Salmson (Canton-Unné) M-9 and a 45'0" wing; 1914 USN seaplane AH-7 had 90hp Curtiss, and a similar wheeled version went to the Army that year [probably AS36].

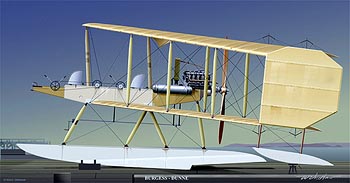

The Burgess-Dunne Aerohydroplane The Burgess-Dunne Aerohydroplane of 1914 was an inherently stable tailless biplane designed by John W. Dunne of England. The Burgess Company of Massachusetts bought the U.S. manufacturing rights and reconfigured it as a waterborne aeroplane.

The Burgess-Dunne Aerohydroplane

The ailerons were rigged to allow independent operation, thus permitting the ailerons to also function as elevators. The U.S. Army Signal Corps purchased Burgess-Dunne No. 3, a wheeled land version, for use at North Island, San Diego, California. A 100 h.p. Curtiss O-X engine was the standard powerplant, but the Signal Corps machine was powered by a 135 h.p. Salmson radial engine

|

© Copyright 1999-2002 CTIE - All Rights Reserved - Caution |